up:: 📥 Sources

type:: #📥/📰

status:: #📥/🟧

tags:: #on/articles

topics:: Marcel Duchamp

Author:: Stephen Jay Gould

Title:: The Substantial Ghost Towards a General Exegesis of Duchamps Artful Wordplays

URL:: "https://www.toutfait.com/issues/issue_2/Articles/gould.html"

Reviewed Date:: 2025-04-15

Finished Year:: 2025

The Substantial Ghost: Towards a General Exegesis of Duchamp's Artful Wordplays

summary:: The essay argues that Marcel Duchamp's frequent use of wordplay is fundamental to understanding his art. Author Stephen Jay Gould posits that these puns, often overlooked, showcase Duchamp's profound creative approach. The analysis explores the multiple layers of meaning in Duchamp's wordplays, particularly focusing on the "A Guest + A Host = A Ghost" example, and categorizes the different types of wordplay Duchamp employed.

Key Points

- Duchamp's pun "A Guest + A Host = A Ghost" highlights the richness and ambiguity characteristic of his wordplays.

- This specific pun functions on several levels, including literal letter combination, definitional contrast, contextual humor, and observation related to exhibitions.

- Duchamp himself valued his verbal punning as inspirational and representative of his artistic methods.

- The essay outlines four categories of Duchamp's wordplay, all centered on how minor sound or spelling changes can create major shifts in meaning.

- His wordplays often create humor by unexpectedly shifting context, emphasizing the contrast between small changes and large effects.

- An analysis of alliteration in "Jeune homme triste dans un train" (Sad Young Man on a Train) reveals layers related to movement, limits, and word origins.

- The essay examines Duchamp's use of combined visual and verbal elements, opposition, and expansion/contraction in his wordplays, citing examples from his notes and art.

- Interpreting Duchamp's wordplays, especially unpublished notes, presents challenges, and the essay acknowledges scholarly work in deciphering them.

Take a look at all of my highlights, denoted here by unique ids. Ignore the single word highlights, some contain definitions below them, those can be combined in a "Words" list with definitions of each which we will do later. Given the other highlights, and the personal notes I made below them for some of them, give me a short essay describing the themes of the article, use quotes from the highlights and include outside sources if you find it helpful.

Thoughts

Amazing essay about Marcel Duchamp, the genius of artistic wordplay

Highlights

id877491048

Duchamp designed the square tinfoil wrappers, and inscribed each little gift to the invitees with a simple and original phrase that may well be regarded as his deepest and richest play on words: A Guest + A Host = A Ghost. 🔗

id877492547

I like words in a poetic sense. Puns for me are like rhymes. ... For me, words are not merely a means of communication. You know, puns have always been considered a low form of wit, but I find them a source of stimulation both because of their actual sound and because of the unexpected meanings attached to the interrelationships of disparate words. For me, this is an infinite field of joy - and it's always right at hand. Sometimes four or five different levels of meaning come through. 🔗

- [N] Duchamp on puns

id877492785

But all these usages proceed from the single principle that tiny variations - whether of sound or of orthography, and often so small as to pass beneath our discernment in the usual human style of lazy or passive reading - can generate enormous, and wonderfully interesting, differences in meaning. 🔗

id877492822

The use of a word in such a way as to suggest two or more meanings or different associations, or the use of two or more words of the same or nearly the same sound with different meanings, so as to produce a humorous effect; a play on words. 🔗

- [N] Definition of "pun"

id877497078

- Anagrams, or extracting different meanings from the same letters rearranged in alternate sequences. 🔗

id877497386

2A. Puns as homonyms. If anagrams produce their large differences in meaning from spatial rearrangement of identical components (leading to a visual joke), then homonymic puns operate as a strict analog in the aural dimension - for the joke now arises from oddly disparate meanings generated by the same sounds (usually spelled differently or parsed into different words). 🔗

id877498073

In a lovely example, far more complex than I first realized, Duchamp drew a rebus in 1925 (Schwarz, number 412) for one of his oft-repeated homonymic puns: nous nous cajolions. Here, he breaks this full phrase ("we flatter (or pet) each other") into two visual parts - a woman caring for a child, representing a nanny (nounou in French, with the exact same pronunciation as nous nous), followed by the more obvious lion behind bars (cage au lion, or lion's cage, pronounced exactly as cajolions).

I only appreciated the depth of Duchamp's construction when I studied the etymology of cajoler in Robert. The probable origin of this verb, meaning to flatter or to wheedle, can be traced to the singing of birds in a cage. Moreover, the derived noun cajolerie specifically identifies the condescending tone that men often adopt in trying to influence women or children. Hence, both images of the rebus specify a historical source for the full phrase thus represented - the woman and child of the first part, followed by the caged animal of the second part. 🔗

- [N] Crazy example of "we flatter each other"

Image: https://www.toutfait.com/issues/issue_2/Articles/po_07.html

id877498097

Marcel Duchamp,

Nous Nous Cajolions, 1943

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. 🔗

id877498311

for Duchamp's best products in this mode, I nominate, for first prize, "do shit again and douche it again" (P.N., 232) as truly identical soundings with opposite meanings (foul it again vs. wash it again); and, for second prize, the delicious bilingual homonym (P.N., 229) "coup de gueule / good girl" (a smack in the face and a well behaved lass - pronounced almost identically, with the first sounding like the second spoken with a French accent 🔗

id877498942

Duchamp frequently split "literature," the aspiration of all wordplaying, into three separate words of nearly the same pronunciation "lits et ratures" (P.N., 224). But these words would annihilate any pretense to creating great written works, for we use our beds ("lits") for the two most frequent activities, sleep and sex, that steal time from our literary struggles - while "ratures" are erasures! (3) 🔗

id877498946

2B. Puns as transpositions (near homonyms). This category encompasses the more subtle and systematic near homonyms (large differences in meaning generated by small alterations in sound) that generally win more respect than truly homonymic puns because they often originate by careful and thoughtful construction, rather than by the sheer accident of an unconsidered alternative meaning for a chosen statement (or a consciously forced and painful likeness in the "ouch" mode of knock-knock jokes). 🔗

id877502769

In the first example, Duchamp asks why a baby at the breast may be compared with first prize in a vegetable contest (P.N., 232): "Le premiere est un souffleur de chair chaude et le second un chou-fleur de serre chaude" - literally, "the first is a blower of warm flesh and the second a cauliflower from a hothouse." The contrast in meaning is wonderfully absurd, but not without some amusing similarity in the great difference - as both cited items are round and warm (the baby's head and the hothouse cauliflower). But the pronounced alteration of meaning arises entirely from a small reciprocal shift in a pair of similar sounds - "s" and "ch" (pronounced "sh") - in two words: for souffleur becomes chou-fleur, changing s to ch, while, later in the phrase, chair becomes serre, changing ch back to s. 🔗

id877503341

Click to enlarge

Marcel Duchamp,

Disk Inscribed with Pun, from Anémic Cinéma, 1926

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. 🔗

id877524506

In a wonderfully complex transposition, involving both sounds and letters (P.N., 225, and as a slight variant, appearing in the form cited here, in the 1939 booklet, Rrose Selavy, that collected 43 Duchampian aphorisms, most published previously and singly), Duchamp inverts the cr-s of a word in the first phrase (crasse) into s-cr in the corresponding word of the second phrase (Sacre). He then inverts the t-m and p-n of a word in the first phrase (tympan) into p-n followed by t-m for a word in the second phrase (Printemps). The result becomes a mordant comment about a famous incident in the long history of public opposition to avant-garde works of art - the angry crowd reaction (including prolonged catcalling and even some throwing of chairs) that followed the premiere of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring in 1913: "La crasse de tympan et non le Sacre de Printemps" - "The filth of the eardrum and not the Rite of Spring." The mocking crowd annihilates Stravinsky's piece by transposition to an ultimate affront upon their aural receptors; (an opponent might also nullify the composition by plugging up his ears so completely that no sound can get through). (4) 🔗

- [N] Crazy example, how did he think of this?

id877525416

the L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) inscribed at the bottom of his mustachioed Mona Lisa, and suggesting the near English reading of "look" but obviously intended primarily to designate the meaning rendered by the names of the letters in their French pronunciation: el-hache-o-o-ku, or "elle a chaud au cul" (she has a hot ass). 🔗

- [N] "She has a hot ass" - mustache Mona Lisa

id877526454

- Generations and Compressions. My final category of wordplay evokes yet another, and quite different, principle used for the same purpose of constructing major disparities from homonyms or minor differences. Many words embody great potential for spinning out a wide range of meanings from a common source - both because the word itself may bear several alternative definitions, and also because the same word, in different combinations or used in different parts of speech, attains several contrasting significances. For example, an old English joke displays the full range for one of our most flexible and pungent words: A ship's captain asks a sailor with no great mechanical expertise to go below and find out why the engine has stalled. The man descends, and finally emerges from the engine room with the following fully comprehensible diagnosis made of an exclamation, an adjective, a noun and a verb: "Fuck, the fucking fuck is fucked." 🔗

id877526581

"Le Sommelier a sommeillé sur un sommier lié de Somalie" - the wine steward (sommelier) napped (sommeillé) on a tied spring mattress (sommier lié) from Somalia (Somalie). 🔗

id877527203

On the edge of this rotary disc, carefully inscribed in elegant industrial perfection, Duchamp wrote one of his favorite, and oft repeated, generative puns: "Esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis" - let us avoid the bruises of the Eskimoes in exquisite words. The text may sound ridiculous, but the pun becomes complex and clever through its union of similar sounds with different spellings. In the four generated phrases of nearly identical sound (esquivons, ecchymoses, Esquimaux and, with inverted syllables, mots exquis), the common sound moze receives different spellings in each of the three words (moses, maux, and mots); while the other nearly common sound of all four words uses three permutations of the first part (es, ek, and eks) with a constant second part (key) - Esquimaux as es-key, ecchymoses as ek-key, and exquis as eks-key. Moreover, and to show Duchamp's care in detail, moze becomes the identical sound of three words only because, in two cases, an elision to the following word (Esquimaux aux, and mots exquis) triggers the voiced "z" of moze in a word that would, if standing alone, be pronounced moe. 🔗

- [N] "Rotary Demisphere", wild example

id877529700

IV. The Ghost Pun as a Brilliant Epitome of All Categories 🔗

id877529739

A Guest + A Host = A Ghost 🔗

id877529867

I could not help wondering if Duchamp enjoyed the power that he gained in removing the "ue" of guest - that is, by taking these letters away in reading their French pronunciation (UÉ or, admittedly approximately, "away") - and then substituting, with an exclamation of surprise ("oh"), the emptiness of zero or "o" to turn his living invitee into a shroud. (Or perhaps, having taken the ue of guest away, leaving g__st as a surrounding shell, Duchamp then followed a common instruction of commercial cooking products: "just add water." Water, in French, is eau, pronounced just as the added letter "o." Water, chemically, is H2O - exactly the added letters to "ghost," with "h" in the second position). 🔗

- [N] Interesting conjectures, but iffy

id877530502

By conjoining the words in a purely physical way, rather than by linking their meanings in a definitional manner, he produces an opposite result. Now the guest and host interact to annihilate each other (that is, to produce a ghost in their joining) rather than to fulfill their shared destiny in interaction! In other words, Duchamp has created a contraction where the definitional result (a ghostly output that annihilates the two living inputs) reinforces the eliminations of letters required to construct the physical result - whereas most contractions yield the opposite effect of compressing two parts into a mutually intensified meaning. (7) 🔗

id877530577

id877530889

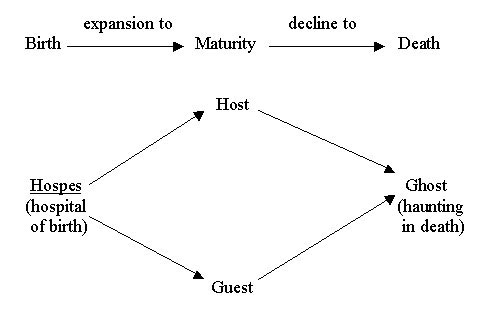

"Guest" and "host" not only sound and look alike, but they also share the same etymological root, despite their later evolution to contrasting aspects of the same concept. Both words originated from the Latin root hospes, from which we also derive such words as hospitality (the shared concept uniting a guest and a host) and hospital. Thus, the ghost pun runs through a full life cycle - beginning as an expanding generation in the first mode of my fourth category, as the original and common root branches (from its birth, perhaps in the hospital of its etymological origin) and then growing in two directions to generate guests and hosts. Duchamp then brings the life cycle to its close in death - thus infusing the entire design with a lovely and dynamic symmetry - by fusing the two words together again (a contraction in the second mode of my fourth category, achieved by a physical amalgamation of letters rather than by a functional union of meaning), and killing both parts in the ghostly conjunction! 🔗

id877531597

by their conjunction, the host annihilates the guest to generate the resulting emptiness of a ghost. The etymological argument - that Duchamp's physical conjunction closes a life cycle of birth, growth, decline and death, by mimicking the original status of the two words as descendants of a single root - strongly intensifies the irony of annihilation. 🔗

id877531631

the additional etymological observation that the English word host includes, under its umbrella of identical spelling and sound, three entirely distinct words of fully independent origin - and that an aspect of each independent host annihilates a guest into a ghost! 🔗

id877532909

- An entirely different word host derives from the Latin hostis, and may designate a crowd or, usually and more specifically, an army - not a friendly bunch, as the most common cognate "hostile" suggests. 🔗

id877532912

In short, this second kind of host designates an opposing army that will certainly, and with maximal efficiency, turn any guest of the other side into a ghost. 🔗

id877532937

- Yet a third meaning of host derives from another completely independent word - hostia, meaning a victim or a sacrifice. 🔗

id877532956

If a guest at my church takes the host at communion, he achieves closer contact with the Holy Ghost who is one (in the trinity) with God the Father and Christ the Son. 🔗

id877532992

infrathin - that effectively invisible plane of separation, through which all products of human brilliance must pass in their transition and promotion from the tiny and palpable into wondrously diversifying realms of ever expanding meaning and signification. 🔗

- [N] infrathin (noun): the subtle, often imperceptible distinction or separation between concepts, ideas, or artistic expressions that influences their interpretation and meaning. 🌫️🔍

id877533112

seek the richness that the human mind can extract from every item in our endlessly complex universe 🔗

id877533127

Keep your eyes and ears - and your mind - open, for the world does lie exposed in a grain of sand, and heaven in a flower. 🔗

id877533213

And so the ghost of Marcel Duchamp, the ultimate (and arrogant) Cartesian rationalist, covering his consummately intellectual ass in a nihilistic shroud of Dada, laughs at us as he urges both his fans and enemies to envelop his sweet little jokes in sharp and multiple layers of meaning. 🔗