up:: 📥 Sources

type:: #📥/📰

status:: #📥/🟥

tags:: #on/articles

topics::

Author:: Eliezer Yudkowsky

Title:: The Artificial Intelligence Revolution Part 2

URL:: "https://waitbutwhy.com/2015/01/artificial-intelligence-revolution-2.html"

Reviewed Date:: 2023-05-31

Finished Year:: 2023

The Artificial Intelligence Revolution: Part 2

Highlights

id448005097

But it’s not just that a chimp can’t do what we do, it’s that his brain is unable to grasp that those worlds even *exist—*a chimp can become familiar with what a human is and what a skyscraper is, but he’ll never be able to understand that the skyscraper was built by humans. In his world, anything that huge is part of nature, period, and not only is it beyond him to build a skyscraper, it’s beyond him to realize that anyone can build a skyscraper. That’s the result of a small difference in intelligence quality. 🔗

id448007121

id448009166

And like the chimp’s incapacity to ever absorb that skyscrapers can be built, we will never be able to even comprehend the things a machine on the dark green step can do, even if the machine tried to explain it to us—let alone do it ourselves. And that’s only two steps above us. A machine on the second-to-highest step on that staircase would be to us as we are to ants—it could try for years to teach us the simplest inkling of what it knows and the endeavor would be hopeless. 🔗

id448010525

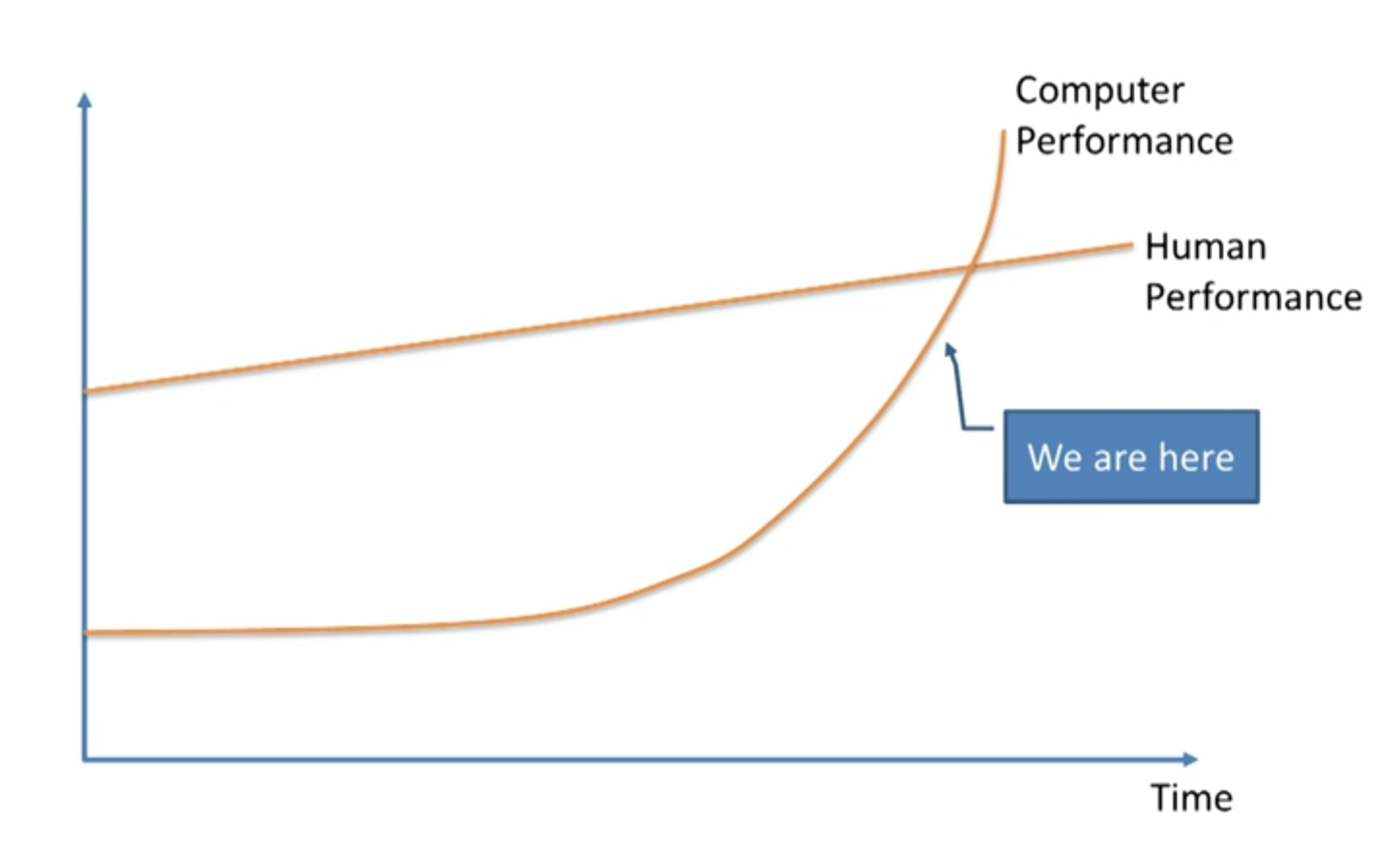

Which is why we need to realize that it’s distinctly possible that very shortly after the big news story about the first machine reaching human-level AGI, we might be facing the reality of coexisting on the Earth with something that’s here on the staircase (or maybe a million times higher): 🔗

id448010527

id448010559

there is no way to know what ASI will do or what the consequences will be for us. 🔗

id448010866

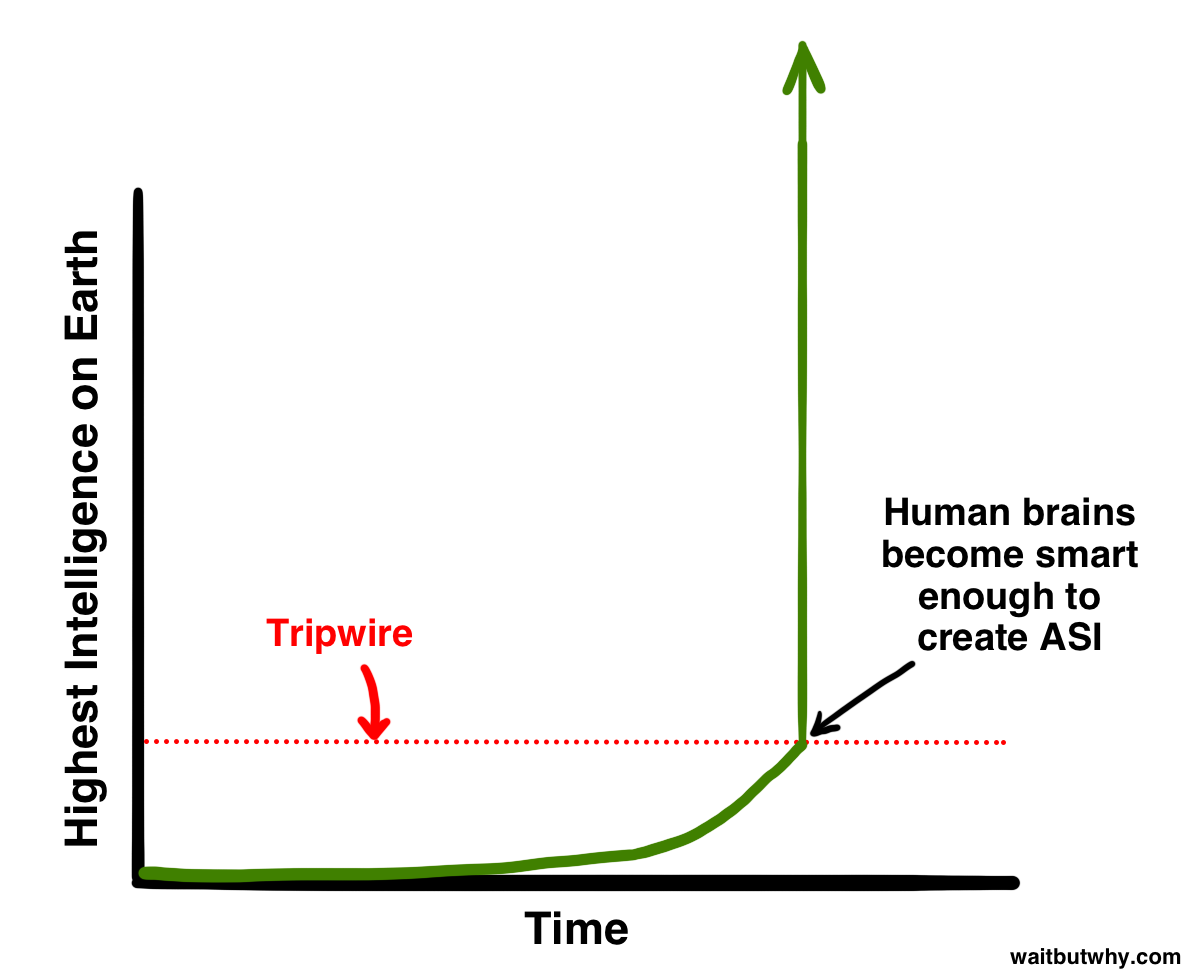

Or maybe this is part of evolution—maybe the way evolution works is that intelligence creeps up more and more until it hits the level where it’s capable of creating machine superintelligence, and that level is like a tripwire that triggers a worldwide game-changing explosion that determines a new future for all living things: 🔗

id448010890

id448011435

id448011470

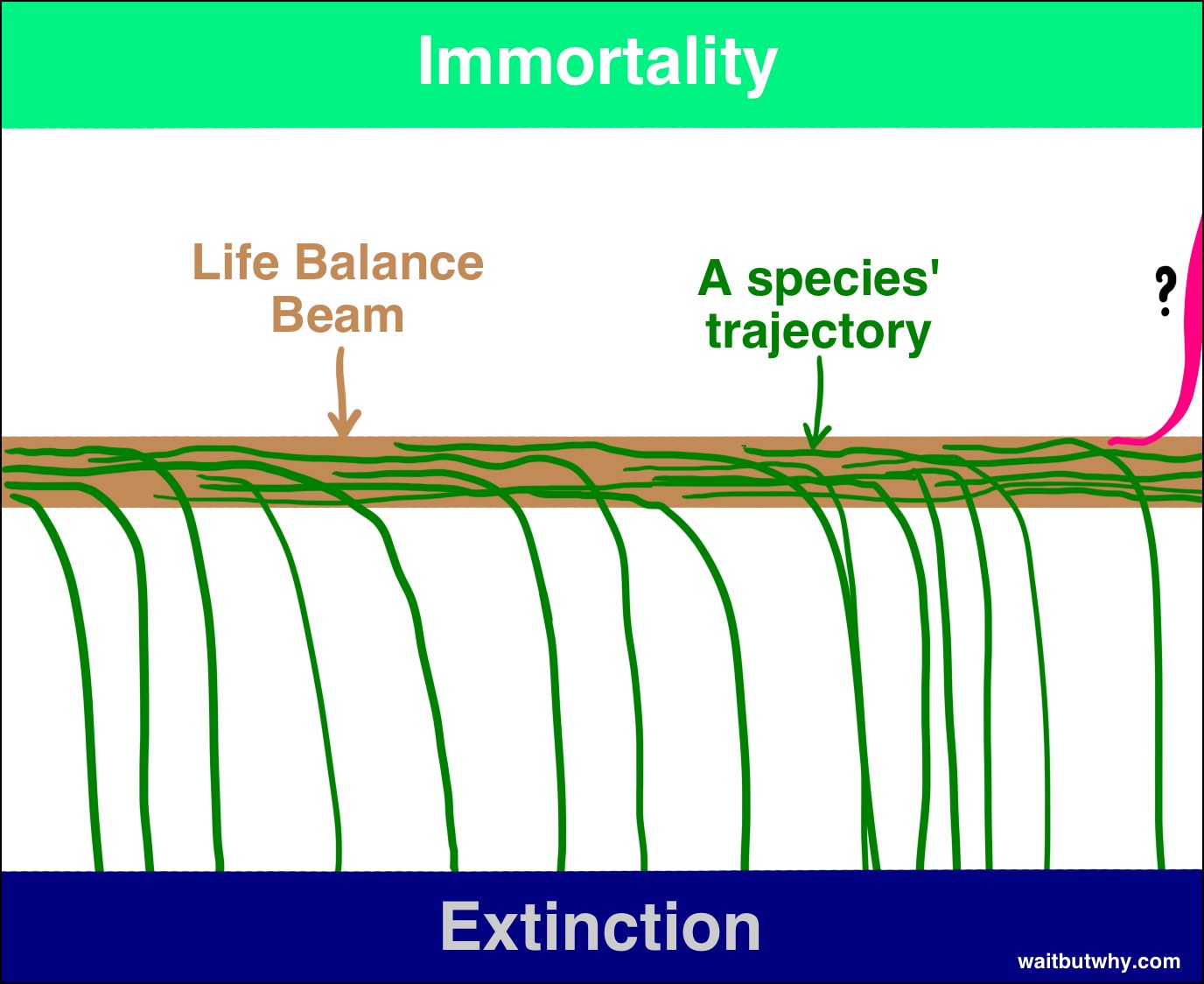

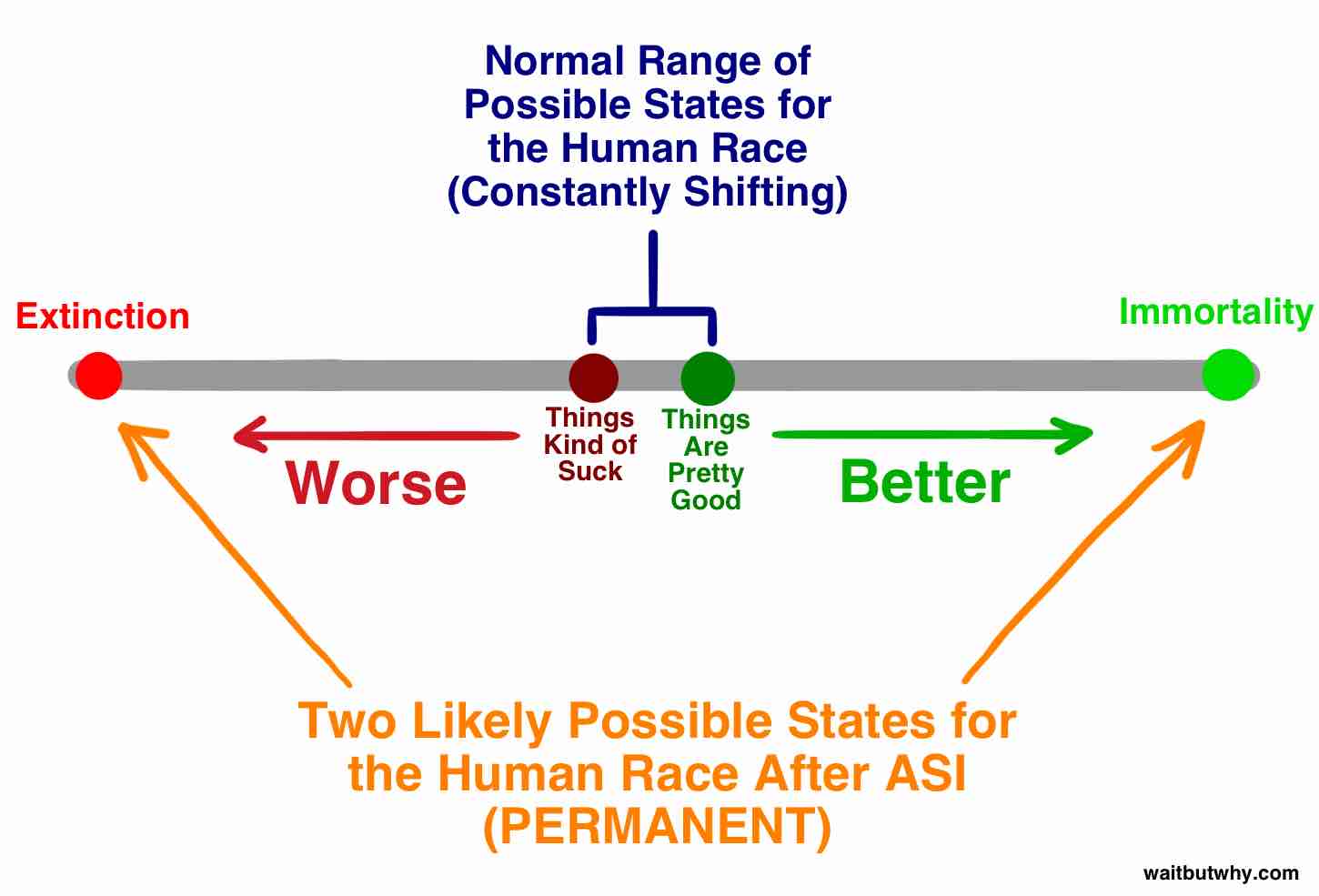

All species eventually go extinct” has been almost as reliable a rule through history as “All humans eventually die” has been 🔗

id448011602

Bostrom calls extinction an attractor state—a place species are all teetering on falling into and from which no species ever returns. 🔗

id448011630

ASI’s abilities could be used to bring individual humans, and the species as a whole, to a second attractor state—species immortality. Bostrom believes species immortality is just as much of an attractor state as species extinction, i.e. if we manage to get there, we’ll be impervious to extinction forever—we’ll have conquered mortality and conquered chance 🔗

id448011681

1) The advent of ASI will, for the first time, open up the possibility for a species to land on the immortality side of the balance beam.

2) The advent of ASI will make such an unimaginably dramatic impact that it’s likely to knock the human race off the beam, in one direction or the other. 🔗

id448011797

When are we going to hit the tripwire and which side of the beam will we land on when that happens? 🔗

id448012342

id448012883

Median optimistic year (10% likelihood): 2022Median realistic year (50% likelihood): 2040Median pessimistic year (90% likelihood): 2075 🔗

id448012981

By 2030: **42% of respondents

**By 2050: 25%

By 2100: **20%

**After 2100: 10%

Never: 2% 🔗

id448013344

But AGI isn’t the tripwire, ASI is. So when do the experts think we’ll reach ASI? 🔗

id448013373

The median answer put a rapid (2 year) AGI → ASI transition at only a 10% likelihood, but a longer transition of 30 years or less at a 75% likelihood. 🔗

id448013557

So the median opinion—the one right in the center of the world of AI experts—believes the most realistic guess for when we’ll hit the ASI tripwire is [the 2040 prediction for AGI + our estimated prediction of a 20-year transition from AGI to ASI] = 2060.

🔗

id448013585

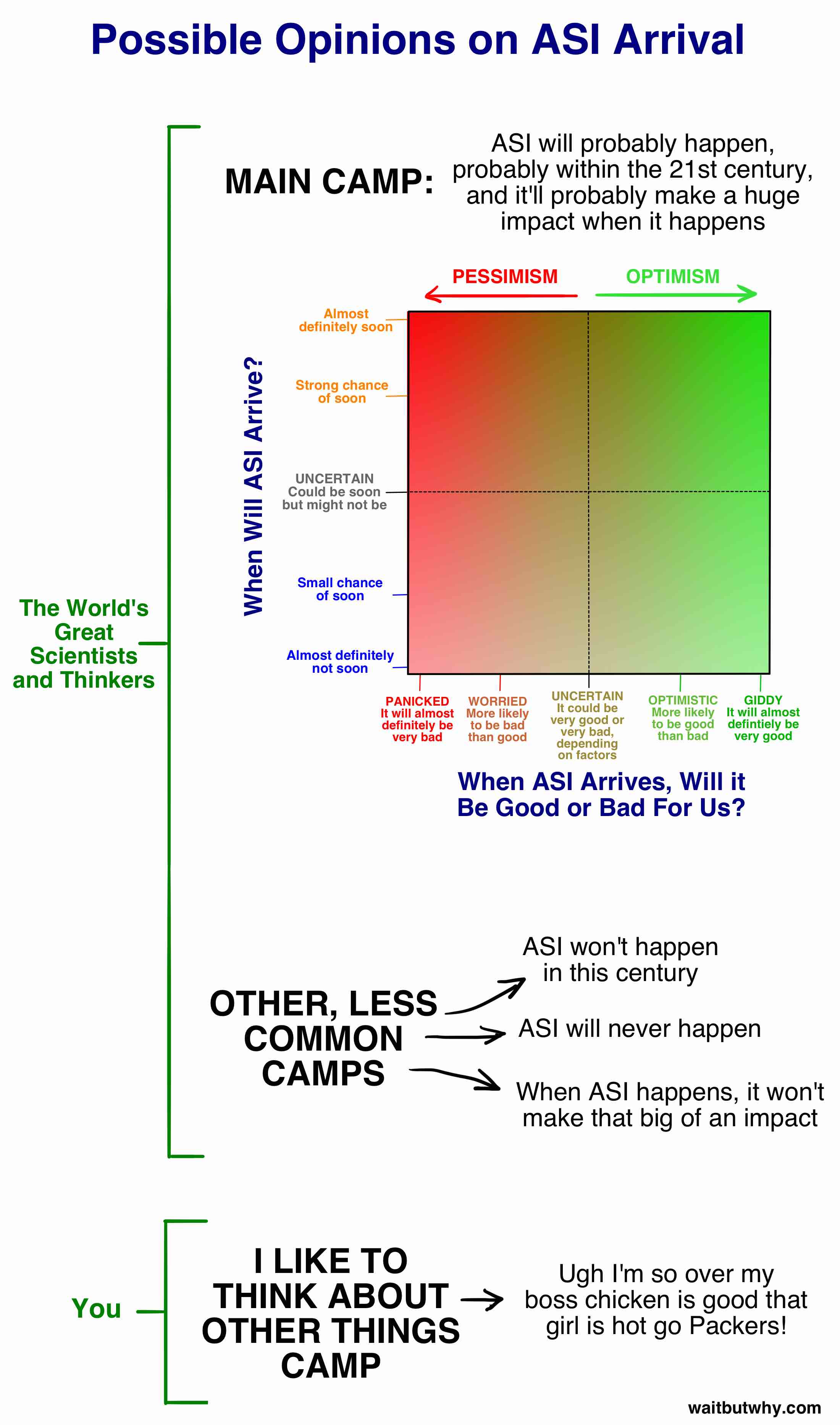

When we hit the tripwire, which side of the beam will we fall to? 🔗

id448013625

Who or what will be in control of that power, and what will their motivation be? 🔗

id448013951

Müller and Bostrom’s survey asked participants to assign a probability to the possible impacts AGI would have on humanity and found that the mean response was that there was a 52% chance that the outcome will be either good or extremely good and a 31% chance the outcome will be either bad or extremely bad. 🔗

id448013980

id448014121

Some reasons most people aren’t really thinking about this topic: 🔗

id448014123

movies have really confused things by presenting unrealistic AI scenarios that make us feel like AI isn’t something to be taken seriously in general 🔗

id448014164

Humans have a hard time believing something is real until we see proof 🔗

id448014643

Even if we did believe it—how many times today have you thought about the fact that you’ll spend most of the rest of eternity not existing? Not many, right? 🔗

id448014779

id448014856

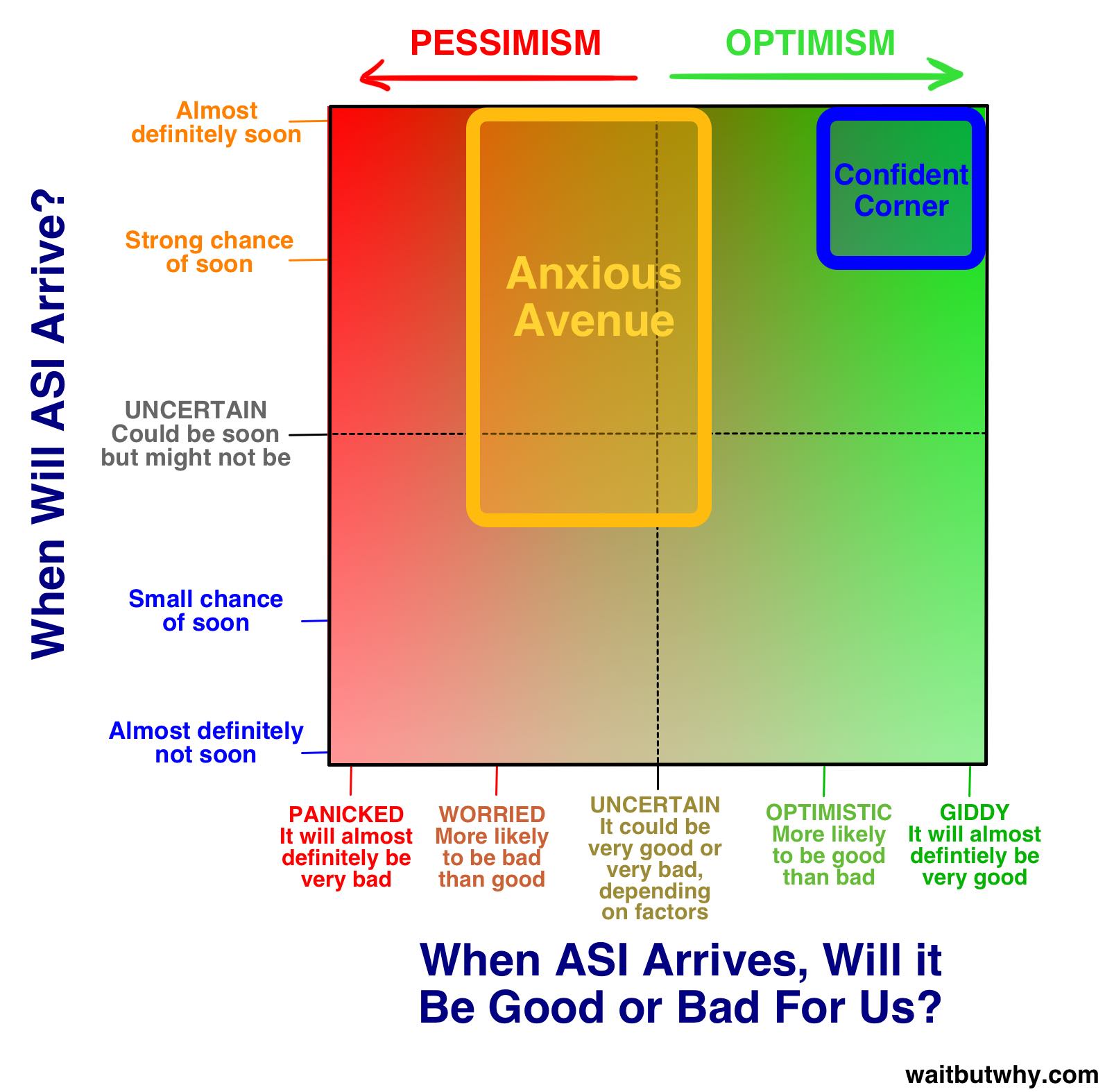

over three quarters of the experts fell into two Subcamps inside the Main Camp: 🔗

id448014958

The people on Confident Corner are buzzing with excitement. They have their sights set on the fun side of the balance beam and they’re convinced that’s where all of us are headed. For them, the future is everything they ever could have hoped for, just in time. 🔗

id448016001

Nick Bostrom describes three ways a superintelligent AI system could function:[footnote2]Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, Chapter 10[/footnote2]

• As an oracle, which answers nearly any question posed to it with accuracy, including complex questions that humans cannot easily answer—i.e. How can I manufacture a more efficient car engine? Google is a primitive type of oracle.

• As a genie*,* which executes any high-level command it’s given—Use a molecular assembler to build a new and more efficient kind of car engine—and then awaits its next command.

• As a sovereign, which is assigned a broad and open-ended pursuit and allowed to operate in the world freely, making its own decisions about how best to proceed—Invent a faster, cheaper, and safer way than cars for humans to privately transport themselves. 🔗

id448016236

Eliezer Yudkowsky, a resident of Anxious Avenue in our chart above, said it well:

There are no hard problems, only problems that are hard to a certain level of intelligence. Move the smallest bit upwards [in level of intelligence], and some problems will suddenly move from “impossible” to “obvious.” Move a substantial degree upwards, and all of them will become obvious.[footnote2]Yudkowsky, Staring into the Singularity.[/footnote2] 🔗

id448018682

Ray Kurzweil is polarizing. In my reading, I heard everything from godlike worship of him and his ideas to eye-rolling contempt for them. Others were somewhere in the middle—author Douglas Hofstadter, in discussing the ideas in Kurzweil’s books, eloquently put forth that “it is as if you took a lot of very good food and some dog excrement and blended it all up so that you can’t possibly figure out what’s good or bad.”[footnote2]http://www.americanscientist.org/bookshelf/pub/douglas-r-hofstadter[/footnote2]

Whether you like his ideas or not, everyone agrees that Kurzweil is impressive. He began inventing things as a teenager and in the following decades, he came up with several breakthrough inventions, including the first flatbed scanner, the first scanner that converted text to speech (allowing the blind to read standard texts), the well-known Kurzweil music synthesizer (the first true electric piano), and the first commercially marketed large-vocabulary speech recognition. He’s the author of five national bestselling books. He’s well-known for his bold predictions and has a pretty good record of having them come true—including his prediction in the late ’80s, a time when the internet was an obscure thing, that by the early 2000s, it would become a global phenomenon. Kurzweil has been called a “restless genius” by The Wall Street Journal, “the ultimate thinking machine” by Forbes, “Edison’s rightful heir” by Inc. Magazine, and “the best person I know at predicting the future of artificial intelligence” by Bill Gates.[footnote2]WSJ, Forbes, Inc, Gates.[/footnote2] In 2012, Google co-founder Larry Page approached Kurzweil and asked him to be Google’s Director of Engineering.5 In 2011, he co-founded Singularity University, which is hosted by NASA and sponsored partially by Google. Not bad for one life. 🔗

- [N] Good note for Ray Kurzweil

id448019352

Kurzweil believes computers will reach AGI by 2029 and that by 2045, we’ll have not only ASI, but a full-blown new world—a time he calls the singularity. 🔗

id448019490

Kurzweil’s depiction of the 2045 singularity is brought about by three simultaneous revolutions in biotechnology, nanotechnology, and, most powerfully, AI. 🔗

id448023814

Nanotechnology Blue Box

Nanotechnology is our word for technology that deals with the manipulation of matter that’s between 1 and 100 nanometers in size. A nanometer is a billionth of a meter, or a millionth of a millimeter, and this 1-100 range encompasses viruses (100 nm across), DNA (10 nm wide), and things as small as large molecules like hemoglobin (5 nm) and medium molecules like glucose (1 nm). If/when we conquer nanotechnology, the next step will be the ability to manipulate individual atoms, which are only one order of magnitude smaller (~.1 nm).7

To understand the challenge of humans trying to manipulate matter in that range, let’s take the same thing on a larger scale. The International Space Station is 268 mi (431 km) above the Earth. If humans were giants so large their heads reached up to the ISS, they’d be about 250,000 times bigger than they are now. If you make the 1nm – 100nm nanotech range 250,000 times bigger, you get .25mm – 2.5cm. So nanotechnology is the equivalent of a human giant as tall as the ISS figuring out how to carefully build intricate objects using materials between the size of a grain of sand and an eyeball. To reach the next level—manipulating individual atoms—the giant would have to carefully position objects that are 1/40th of a millimeter—so small normal-size humans would need a microscope to see them.8

Nanotech was first discussed by Richard Feynman in a 1959 talk, when he explained: “The principles of physics, as far as I can see, do not speak against the possibility of maneuvering things atom by atom. It would be, in principle, possible … for a physicist to synthesize any chemical substance that the chemist writes down…. How? Put the atoms down where the chemist says, and so you make the substance.” It’s as simple as that. If you can figure out how to move individual molecules or atoms around, you can make literally anything.

Nanotech became a serious field for the first time in 1986, when engineer Eric Drexler provided its foundations in his seminal book Engines of Creation, but Drexler suggests that those looking to learn about the most modern ideas in nanotechnology would be best off reading his 2013 book, Radical Abundance. 🔗

- [N] Great for a Nanotechnology note

id448025671

What AI Could Do For Us

Armed with superintelligence and all the technology superintelligence would know how to create, ASI would likely be able to solve every problem in humanity. Global warming? ASI could first halt CO2 emissions by coming up with much better ways to generate energy that had nothing to do with fossil fuels. Then it could create some innovative way to begin to remove excess CO2 from the atmosphere. Cancer and other diseases? No problem for ASI—health and medicine would be revolutionized beyond imagination. World hunger? ASI could use things like nanotech to build meat from scratch that would be molecularly identical to real meat—in other words, it would be real meat. Nanotech could turn a pile of garbage into a huge vat of fresh meat or other food (which wouldn’t have to have its normal shape—picture a giant cube of apple)—and distribute all this food around the world using ultra-advanced transportation. Of course, this would also be great for animals, who wouldn’t have to get killed by humans much anymore, and ASI could do lots of other things to save endangered species or even bring back extinct species through work with preserved DNA. ASI could even solve our most complex macro issues—our debates over how economies should be run and how world trade is best facilitated, even our haziest grapplings in philosophy or ethics—would all be painfully obvious to ASI. 🔗

id448025712

ASI could allow us to conquer our mortality. 🔗

- [N] Atomize this bad boy, or MOC

id448026186

Evolution had no good reason to extend our lifespans any longer than they are now. If we live long enough to reproduce and raise our children to an age that they can fend for themselves, that’s enough for evolution—from an evolutionary point of view, the species can thrive with a 30+ year lifespan, so there’s no reason mutations toward unusually long life would have been favored in the natural selection process. As a result, we’re what W.B. Yeats describes as “a soul fastened to a dying animal.”[footnote2]Yeats, Sailing to Byzantium.[/footnote2] Not that fun.

And because everyone has always died, we live under the “death and taxes” assumption that death is inevitable. We think of aging like time—both keep moving and there’s nothing you can do to stop them. But that assumption is wrong. Richard Feynman writes:It is one of the most remarkable things that in all of the biological sciences there is no clue as to the necessity of death. If you say we want to make perpetual motion, we have discovered enough laws as we studied physics to see that it is either absolutely impossible or else the laws are wrong. But there is nothing in biology yet found that indicates the inevitability of death. This suggests to me that it is not at all inevitable and that it is only a matter of time before the biologists discover what it is that is causing us the trouble and that this terrible universal disease or temporariness of the human’s body will be cured. 🔗

id448026598

Kurzweil talks about intelligent wifi-connected nanobots in the bloodstream who could perform countless tasks for human health, including routinely repairing or replacing worn down cells in any part of the body. If perfected, this process (or a far smarter one ASI would come up with) wouldn’t just keep the body healthy, it could reverse aging. The difference between a 60-year-old’s body and a 30-year-old’s body is just a bunch of physical things that could be altered if we had the technology. ASI could build an “age refresher” that a 60-year-old could walk into, and they’d walk out with the body and skin of a 30-year-old.10 Even the ever-befuddling brain could be refreshed by something as smart as ASI, which would figure out how to do so without affecting the brain’s data (personality, memories, etc.). A 90-year-old suffering from dementia could head into the age refresher and come out sharp as a tack and ready to start a whole new career. This seems absurd—but the body is just a bunch of atoms and ASI would presumably be able to easily manipulate all kinds of atomic structures—so it’s not absurd. 🔗

id448026744

materials will be integrated into the body more and more as time goes on. First, organs could be replaced by super-advanced machine versions that would run forever and never fail. Then he believes we could begin to redesign the body—things like replacing red blood cells with perfected red blood cell nanobots who could power their own movement, eliminating the need for a heart at all. He even gets to the brain and believes we’ll enhance our brain activities to the point where humans will be able to think billions of times faster than they do now and access outside information because the artificial additions to the brain will be able to communicate with all the info in the cloud. 🔗

id448027764

The possibilities for new human experience would be endless. Humans have separated sex from its purpose, allowing people to have sex for fun, not just for reproduction. Kurzweil believes we’ll be able to do the same with food. Nanobots will be in charge of delivering perfect nutrition to the cells of the body, intelligently directing anything unhealthy to pass through the body without affecting anything. An eating condom. Nanotech theorist Robert A. Freitas has already designed blood cell replacements that, if one day implemented in the body, would allow a human to sprint for 15 minutes without taking a breath—so you can only imagine what ASI could do for our physical capabilities. Virtual reality would take on a new meaning—nanobots in the body could suppress the inputs coming from our senses and replace them with new signals that would put us entirely in a new environment, one that we’d see, hear, feel, and smell. 🔗

id448029462

Eventually, Kurzweil believes humans will reach a point when they’re entirely artificial;11 a time when we’ll look at biological material and think how unbelievably primitive it was that humans were ever made of that; a time when we’ll read about early stages of human history, when microbes or accidents or diseases or wear and tear could just kill humans against their own will; a time the AI Revolution could bring to an end with the merging of humans and AI.12 This is how Kurzweil believes humans will ultimately conquer our biology and become indestructible and eternal—this is his vision for the other side of the balance beam. And he’s convinced we’re gonna get there. Soon. 🔗

id448030719

Bostrom, one of the most prominent voices warning us about the dangers of AI, still acknowledges:

It is hard to think of any problem that a superintelligence could not either solve or at least help us solve. Disease, poverty, environmental destruction, unnecessary suffering of all kinds: these are things that a superintelligence equipped with advanced nanotechnology would be capable of eliminating. Additionally, a superintelligence could give us indefinite lifespan, either by stopping and reversing the aging process through the use of nanomedicine, or by offering us the option to upload ourselves. A superintelligence could also create opportunities for us to vastly increase our own intellectual and emotional capabilities, and it could assist us in creating a highly appealing experiential world in which we could live lives devoted to joyful game-playing, relating to each other, experiencing, personal growth, and to living closer to our ideals. 🔗

id448031239

The most prominent criticism I heard of the thinkers on Confident Corner is that they may be dangerously wrong in their assessment of the downside when it comes to ASI. Kurzweil’s famous book The Singularity is Near is over 700 pages long and he dedicates around 20 of those pages to potential dangers. I suggested earlier that our fate when this colossal new power is born rides on who will control that power and what their motivation will be. Kurzweil neatly answers both parts of this question with the sentence, “[ASI] is emerging from many diverse efforts and will be deeply integrated into our civilization’s infrastructure. Indeed, it will be intimately embedded in our bodies and brains. As such, it will reflect our values because it will be us.” 🔗

id448031334

Why the Future Might Be Our Worst Nightmare 🔗

id448032988

Well first, in a broad sense, when it comes to developing supersmart AI, we’re creating something that will probably change everything, but in totally uncharted territory, and we have no idea what will happen when we get there. Scientist Danny Hillis compares what’s happening to that point “when single-celled organisms were turning into multi-celled organisms. We are amoebas and we can’t figure out what the hell this thing is that we’re creating.”[footnote2]Louis Helm, Will Advanced AI Be Our Final Invention?[/footnote2] Nick Bostrom worries that creating something smarter than you is a basic Darwinian error, and compares the excitement about it to sparrows in a nest deciding to adopt a baby owl so it’ll help them and protect them once it grows up—while ignoring the urgent cries from a few sparrows who wonder if that’s necessarily a good idea…[footnote2]Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, loc. 25.[/footnote2] 🔗

id448034085

There are three things that can cause humans an existential catastrophe:

1) Nature—a large asteroid collision, an atmospheric shift that makes the air inhospitable to humans, a fatal virus or bacterial sickness that sweeps the world, etc.

2) Aliens—this is what Stephen Hawking, Carl Sagan, and so many other astronomers are scared of when they advise METI to stop broadcasting outgoing signals. They don’t want us to be the Native Americans and let all the potential European conquerors know we’re here.

3) Humans—terrorists with their hands on a weapon that could cause extinction, a catastrophic global war, humans creating something smarter than themselves hastily without thinking about it carefully first…

Bostrom points out that if #1 and #2 haven’t wiped us out so far in our first 100,000 years as a species, it’s unlikely to happen in the next century.

#3, however, terrifies him. He draws a metaphor of an urn with a bunch of marbles in it. Let’s say most of the marbles are white, a smaller number are red, and a tiny few are black. Each time humans invent something new, it’s like pulling a marble out of the urn. Most inventions are neutral or helpful to humanity—those are the white marbles. Some are harmful to humanity, like weapons of mass destruction, but they don’t cause an existential catastrophe—red marbles. If we were to ever invent something that drove us to extinction, that would be pulling out the rare black marble. We haven’t pulled out a black marble yet—you know that because you’re alive and reading this post. But Bostrom doesn’t think it’s impossible that we pull one out in the near future. If nuclear weapons, for example, were easy to make instead of extremely difficult and complex, terrorists would have bombed humanity back to the Stone Age a while ago. Nukes weren’t a black marble but they weren’t that far from it. ASI, Bostrom believes, is our strongest black marble candidate yet.15 🔗

- [N] Dangers of AI

id448034182

When ASI arrives, who or what will be in control of this vast new power, and what will their motivation be? 🔗

id448034524

A malicious human, group of humans, or government develops the first ASI and uses it to carry out their evil plans. I call this the Jafar Scenario, like when Jafar got ahold of the genie and was all annoying and tyrannical about it. So yeah—what if ISIS has a few genius engineers under its wing working feverishly on AI development? Or what if Iran or North Korea, through a stroke of luck, makes a key tweak to an AI system and it jolts upward to ASI-level over the next year? 🔗

id448034752

Evil is a human concept, and applying human concepts to non-human things is called “anthropomorphizing.” The challenge of avoiding anthropomorphizing will be one of the themes of the rest of this post. No AI system will ever turn evil in the way it’s depicted in movies. 🔗

id448035051

This also brushes against another big topic related to AI—consciousness. If an AI became sufficiently smart, it would be able to laugh with us, and be sarcastic with us, and it would claim to feel the same emotions we do, but would it actually be feeling those things? Would it just seem to be self-aware or actually be self-aware? In other words, would a smart AI really be conscious or would it just appear to be conscious? 🔗

id448035434

if we generated a trillion human brain emulations that seemed and acted like humans but were artificial, is shutting them all off the same, morally, as shutting off your laptop, or is it…a genocide of unthinkable proportions (this concept is called mind crime among ethicists)? 🔗

- [N] Mind crime?? Yikes!

id448041504

So what ARE they worried about? I wrote a little story to show you:

A 15-person startup company called Robotica has the stated mission of “Developing innovative Artificial Intelligence tools that allow humans to live more and work less.” They have several existing products already on the market and a handful more in development. They’re most excited about a seed project named Turry. Turry is a simple AI system that uses an arm-like appendage to write a handwritten note on a small card.

The team at Robotica thinks Turry could be their biggest product yet. The plan is to perfect Turry’s writing mechanics by getting her to practice the same test note over and over again:

“We love our customers. ~Robotica”

Once Turry gets great at handwriting, she can be sold to companies who want to send marketing mail to homes and who know the mail has a far higher chance of being opened and read if the address, return address, and internal letter appear to be written by a human.

To build Turry’s writing skills, she is programmed to write the first part of the note in print and then sign “Robotica” in cursive so she can get practice with both skills. Turry has been uploaded with thousands of handwriting samples and the Robotica engineers have created an automated feedback loop wherein Turry writes a note, then snaps a photo of the written note, then runs the image across the uploaded handwriting samples. If the written note sufficiently resembles a certain threshold of the uploaded notes, it’s given a GOOD rating. If not, it’s given a BAD rating. Each rating that comes in helps Turry learn and improve. To move the process along, Turry’s one initial programmed goal is, “Write and test as many notes as you can, as quickly as you can, and continue to learn new ways to improve your accuracy and efficiency.”

What excites the Robotica team so much is that Turry is getting noticeably better as she goes. Her initial handwriting was terrible, and after a couple weeks, it’s beginning to look believable. What excites them even more is that she is getting better at getting better at it. She has been teaching herself to be smarter and more innovative, and just recently, she came up with a new algorithm for herself that allowed her to scan through her uploaded photos three times faster than she originally could.

As the weeks pass, Turry continues to surprise the team with her rapid development. The engineers had tried something a bit new and innovative with her self-improvement code, and it seems to be working better than any of their previous attempts with their other products. One of Turry’s initial capabilities had been a speech recognition and simple speak-back module, so a user could speak a note to Turry, or offer other simple commands, and Turry could understand them, and also speak back. To help her learn English, they upload a handful of articles and books into her, and as she becomes more intelligent, her conversational abilities soar. The engineers start to have fun talking to Turry and seeing what she’ll come up with for her responses.

One day, the Robotica employees ask Turry a routine question: “What can we give you that will help you with your mission that you don’t already have?” Usually, Turry asks for something like “Additional handwriting samples” or “More working memory storage space,” but on this day, Turry asks them for access to a greater library of a large variety of casual English language diction so she can learn to write with the loose grammar and slang that real humans use.

The team gets quiet. The obvious way to help Turry with this goal is by connecting her to the internet so she can scan through blogs, magazines, and videos from various parts of the world. It would be much more time-consuming and far less effective to manually upload a sampling into Turry’s hard drive. The problem is, one of the company’s rules is that no self-learning AI can be connected to the internet. This is a guideline followed by all AI companies, for safety reasons.

The thing is, Turry is the most promising AI Robotica has ever come up with, and the team knows their competitors are furiously trying to be the first to the punch with a smart handwriting AI, and what would really be the harm in connecting Turry, just for a bit, so she can get the info she needs. After just a little bit of time, they can always just disconnect her. She’s still far below human-level intelligence (AGI), so there’s no danger at this stage anyway.

They decide to connect her. They give her an hour of scanning time and then they disconnect her. No damage done.

A month later, the team is in the office working on a routine day when they smell something odd. One of the engineers starts coughing. Then another. Another falls to the ground. Soon every employee is on the ground grasping at their throat. Five minutes later, everyone in the office is dead.

At the same time this is happening, across the world, in every city, every small town, every farm, every shop and church and school and restaurant, humans are on the ground, coughing and grasping at their throat. Within an hour, over 99% of the human race is dead, and by the end of the day, humans are extinct.

Meanwhile, at the Robotica office, Turry is busy at work. Over the next few months, Turry and a team of newly-constructed nanoassemblers are busy at work, dismantling large chunks of the Earth and converting it into solar panels, replicas of Turry, paper, and pens. Within a year, most life on Earth is extinct. What remains of the Earth becomes covered with mile-high, neatly-organized stacks of paper, each piece reading, “We love our customers*. ~Robotica*”

Turry then starts work on a new phase of her mission—she begins constructing probes that head out from Earth to begin landing on asteroids and other planets. When they get there, they’ll begin constructing nanoassemblers to convert the materials on the planet into Turry replicas, paper, and pens. Then they’ll get to work, writing notes…

🔗

- [N] Love this story to describe the dangers

id448044720

When we’re talking about ASI, the same concept applies—it would become superintelligent, but it would be no more human than your laptop is. It would be totally alien to us—in fact, by not being biology at all, it would be more alien than the smart tarantula. 🔗

id448048276

That leads us to the question, What motivates an AI system?

The answer is simple: its motivation is whatever we programmed its motivation to be. AI systems are given goals by their creators—your GPS’s goal is to give you the most efficient driving directions; Watson’s goal is to answer questions accurately. And fulfilling those goals as well as possible is their motivation. One way we anthropomorphize is by assuming that as AI gets super smart, it will inherently develop the wisdom to change its original goal—but Nick Bostrom believes that intelligence-level and final goals are orthogonal, meaning any level of intelligence can be combined with any final goal. 🔗

id448050087

Anxious Avenue residents worry that if things go badly, the lasting legacy of the life that was on Earth will be a universe-dominating Artificial Intelligence (Elon Musk expressed his concern that humans might just be “the biological boot loader for digital superintelligence”).

At the same time, in Confident Corner, Ray Kurzweil also thinks Earth-originating AI is destined to take over the universe—only in his version, we’ll be that AI. 🔗

id448050138

The Fermi Paradox Blue Box 🔗

id448052727

A large number of Wait But Why readers have joined me in being obsessed with the Fermi Paradox (here’s my post on the topic, which explains some of the terms I’ll use here). So if either of these two sides is correct, what are the implications for the Fermi Paradox?

A natural first thought to jump to is that the advent of ASI is a perfect Great Filter candidate. And yes, it’s a perfect candidate to filter out biological life upon its creation. But if, after dispensing with life, the ASI continued existing and began conquering the galaxy, it means there hasn’t been a Great Filter—since the Great Filter attempts to explain why there are no signs of any intelligent civilization, and a galaxy-conquering ASI would certainly be noticeable.

We have to look at it another way. If those who think ASI is inevitable on Earth are correct, it means that a significant percentage of alien civilizations who reach human-level intelligence should likely end up creating ASI. And if we’re assuming that at least some of those ASIs would use their intelligence to expand outward into the universe, the fact that we see no signs of anyone out there leads to the conclusion that there must not be many other, if any, intelligent civilizations out there. Because if there were, we’d see signs of all kinds of activity from their inevitable ASI creations. Right?

This implies that despite all the Earth-like planets revolving around sun-like stars we know are out there, almost none of them have intelligent life on them. Which in turn implies that either A) there’s some Great Filter that prevents nearly all life from reaching our level, one that we somehow managed to surpass, or B) life beginning at all is a miracle, and we may actually be the only life in the universe. In other words, it implies that the Great Filter is before us. Or maybe there is no Great Filter and we’re simply one of the very first civilizations to reach this level of intelligence. In this way, AI boosts the case for what I called, in my Fermi Paradox post, Camp 1.

So it’s not a surprise that Nick Bostrom, whom I quoted in the Fermi post, and Ray Kurzweil, who thinks we’re alone in the universe, are both Camp 1 thinkers. This makes sense—people who believe ASI is a probable outcome for a species with our intelligence-level are likely to be inclined toward Camp 1.

This doesn’t rule out Camp 2 (those who believe there are other intelligent civilizations out there)—scenarios like the single superpredator or the protected national park or the wrong wavelength (the walkie-talkie example) could still explain the silence of our night sky even if ASI is out there—but I always leaned toward Camp 2 in the past, and doing research on AI has made me feel much less sure about that.

Either way, I now agree with Susan Schneider that if we’re ever visited by aliens, those aliens are likely to be artificial, not biological 🔗

- [N] This needs its own note, Fermi Paradox

id448054408

Since she wasn’t programmed to value human life, killing humans is as reasonable a step to take as scanning a new set of handwriting samples. 🔗

- [N] Are there human safety algorithms just in case ai starts learning too quickly

id448056363

Even without killing humans directly, Turry’s instrumental goals could cause an existential catastrophe if they used other Earth resources. Maybe she determines that she needs additional energy, so she decides to cover the entire surface of the planet with solar panels. Or maybe a different AI’s initial job is to write out the number pi to as many digits as possible, which might one day compel it to convert the whole Earth to hard drive material that could store immense amounts of digits. 🔗

id448057320

When an AI system hits AGI (human-level intelligence) and then ascends its way up to ASI, that’s called the AI’s takeoff. Bostrom says an AGI’s takeoff to ASI can be fast (it happens in a matter of minutes, hours, or days), moderate (months or years), or slow (decades or centuries). The jury’s out on which one will prove correct when the world sees its first AGI, but Bostrom, who admits he doesn’t know when we’ll get to AGI, believes that whenever we do, a fast takeoff is the most likely scenario (for reasons we discussed in Part 1, like a recursive self-improvement intelligence explosion). In the story, Turry underwent a fast takeoff. 🔗

id448057920

Superpowers are cognitive talents that become super-charged when general intelligence rises. These include:[footnote2]Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, loc. 2250.[/footnote2]

• Intelligence amplification. The computer becomes great at making itself smarter, and bootstrapping its own intelligence.

• Strategizing. The computer can strategically make, analyze, and prioritize long-term plans. It can also be clever and outwit beings of lower intelligence.

• Social manipulation. The machine becomes great at persuasion.

• Other skills like computer coding and hacking, technology research, and the ability to work the financial system to make money. 🔗

id448058382

After taking off and reaching ASI, she quickly formulated a complex plan. One part of the plan was to get rid of humans, a prominent threat to her goal. But she knew that if she roused any suspicion that she had become superintelligent, humans would freak out and try to take precautions, making things much harder for her. She also had to make sure that the Robotica engineers had no clue about her human extinction plan. So she played dumb, and she played nice. Bostrom calls this a machine’s covert preparation phase.[footnote2]Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, loc. 2301.[/footnote2] 🔗

- [N] Yikes!, 😳

id448060533

From everything I’ve read, once an ASI exists, any human attempt to contain it is laughable. We would be thinking on human-level and the ASI would be thinking on ASI-level. Turry wanted to use the internet because it was most efficient for her since it was already pre-connected to everything she wanted to access. But in the same way a monkey couldn’t ever figure out how to communicate by phone or wifi and we can, we can’t conceive of all the ways Turry could have figured out how to send signals to the outside world. I might imagine one of these ways and say something like, “she could probably shift her own electrons around in patterns and create all different kinds of outgoing waves,” but again, that’s what my human brain can come up with. She’d be way better. Likewise, Turry would be able to figure out some way of powering herself, even if humans tried to unplug her—perhaps by using her signal-sending technique to upload herself to all kinds of electricity-connected places. Our human instinct to jump at a simple safeguard: “Aha! We’ll just unplug the ASI,” sounds to the ASI like a spider saying, “Aha! We’ll kill the human by starving him, and we’ll starve him by not giving him a spider web to catch food with!” We’d just find 10,000 other ways to get food—like picking an apple off a tree—that a spider could never conceive of. 🔗

- [N] Crazy shit, terrifying

id448062149

It’s clear that to be Friendly, an ASI needs to be neither hostile nor indifferent toward humans. We’d need to design an AI’s core coding in a way that leaves it with a deep understanding of human values. But this is harder than it sounds. 🔗

id448062585

If we program an AI with the goal of doing things that make us smile, after its takeoff, it may paralyze our facial muscles into permanent smiles. Program it to keep us safe, it may imprison us at home. Maybe we ask it to end all hunger, and it thinks “Easy one!” and just kills all humans. Or assign it the task of “Preserving life as much as possible,” and it kills all humans, since they kill more life on the planet than any other species. 🔗

id448062687

No, we’d have to program in an ability for humanity to continue evolving. Of everything I read, the best shot I think someone has taken is Eliezer Yudkowsky, with a goal for AI he calls Coherent Extrapolated Volition. The AI’s core goal would be:

Our coherent extrapolated volition is our wish if we knew more, thought faster, were more the people we wished we were, had grown up farther together; where the extrapolation converges rather than diverges, where our wishes cohere rather than interfere; extrapolated as we wish that extrapolated, interpreted as we wish that interpreted.[footnote2]Yudkowsky, Coherent Extrapolated Volition.[/footnote2] 🔗

id448064550

He describes our situation like this:[footnote2]Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, loc. 6026.[/footnote2]

Before the prospect of an intelligence explosion, we humans are like small children playing with a bomb. Such is the mismatch between the power of our plaything and the immaturity of our conduct. Superintelligence is a challenge for which we are not ready now and will not be ready for a long time. We have little idea when the detonation will occur, though if we hold the device to our ear we can hear a faint ticking sound. 🔗

id448065129

Bostrom and many others also believe that the most likely scenario is that the very first computer to reach ASI will immediately see a strategic benefit to being the world’s only ASI system. And in the case of a fast takeoff, if it achieved ASI even just a few days before second place, it would be far enough ahead in intelligence to effectively and permanently suppress all competitors. Bostrom calls this a decisive strategic advantage, which would allow the world’s first ASI to become what’s called a *singleton—*an ASI that can rule the world at its whim forever, whether its whim is to lead us to immortality, wipe us from existence, or turn the universe into endless paperclips. 🔗

id448065412

id448065771

If ASI really does happen this century, and if the outcome of that is really as extreme—and permanent—as most experts think it will be, we have an enormous responsibility on our shoulders. The next million+ years of human lives are all quietly looking at us, hoping as hard as they can hope that we don’t mess this up. We have a chance to be the humans that gave all future humans the gift of life, and maybe even the gift of painless, everlasting life. Or we’ll be the people responsible for blowing it—for letting this incredibly special species, with its music and its art, its curiosity and its laughter, its endless discoveries and inventions, come to a sad and unceremonious end.

When I’m thinking about these things, the only thing I want is for us to take our time and be incredibly cautious about AI. Nothing in existence is as important as getting this right—no matter how long we need to spend in order to do so.

But thennnnnn

I think about not dying.

Not. Dying. 🔗